The economic-financial crisis of 2008 has produced, if nothing else, grist for the financial press. Bernard Madoff’s alleged $50 billion scam and the assertion that we need a mega-Keynesian stimulus package— the bigger, the better—represent two of today’s favorite topics. In an attempt to make their reportage and opinions more interesting, the authors often attempt to link historical episodes to their Madoff and stimulus stories.

John Law and his Mississippi Company, which was established in 1717 and collapsed in 1720, are standard references that accompany Madoff’s alleged Ponzi scheme. In fact, the only obvious connection between Law’s Mississippi Company and Madoff’s operations is that their values went up and then down. This fact fails to merit mention, however.

What merits attention is that Law was an economist of note and a precursor to John Maynard Keynes and Keynesian economics. Indeed, Law’s Essay on a Land Bank (1704) and Money and Trade (1705) brought high praise from no less than Joseph Schumpeter, who wrote in A History of Economic Analysis: “John Law (1671-1729) I have always felt in a class by himself. He worked out the economics of his projects with a brilliance and, yes, profundity, which places him in the front ranks of monetary theorists of all time.”

John Law’s link to today’s economic and financial turmoil is a Law-Keynes linkage. Like Keynes, Law thought the economy could be stimulated and that growth rates could be permanently elevated through active monetary, fiscal and exchange-rate policies. In short, both economists supported the idea of an active, interventionist government. That said, Keynes curiously avoids mentioning Law, when noting the antecedents to the ideas contained in The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money (1936). Perhaps Keynes didn’t want to be associated with Law’s Mississippi System—a grand project which ended in failure.

The opportunity for Law to implement his ideas arose after Law learned that his good friend, the Duc d’ Orleans, had become the Regent of France. In 1710, the Scotsman emigrated from London to Paris. France was in financial trouble. Among other things, it was in partial default on its bonds. In consequence, the Regent was susceptible to Law’s proposals.

In June 1716, Law launched his first big project. It was then that the Banque Générale was established. It issued paper money which was not fully backed by specie (gold or silver). Instead, government bonds were used to back 50% of the paper money issued by the Banque Générale. This fractional reserve setup was approved by the Crown and the Banque’s paper money was granted legal tender status.

This represented a breakthrough for Law because one of his ideas was to replace specie-based banking systems with credit based systems. Instead of counterbalancing banks’ liabilities (paper money and deposits) with gold or silver assets, the liabilities in a credit-based system would be counterbalanced with loans. The accompanying table highlights the differences between these two systems.

Interestingly, the international monetary system today looks a great deal like the credit-based system envisioned by Law. Indeed, in 1971—300 years after John Law’s birth—the international monetary system abandoned the last vestiges of the gold standard. John Law’s next venture was the establishment of the Mississippi Company. It was granted monopoly rights for trade and development in France’s Louisiana and Canadian territories. And through a series of takeovers and mergers, it became a giant holding company which controlled a vast empire of French trading companies. In addition, the Mississippi Company took over most of the financial functions of the Crown. These included the sole right to coin money, to collect all direct and indirect taxes and to manage the Crown’s debt.

When it came to debt management, Law displayed his flair for innovation. The Mississippi Company was created, in part, to facilitate a debt-for-equity swap in which the Company’s shares were issued in exchange for the Crown’s debt. In consequence, the Crown was able to unload its entire stock of high-yielding debt. The British, not to be outdone by the French, followed Law’s lead and allowed the South Sea Company to assume the bulk of the British government’s debt.

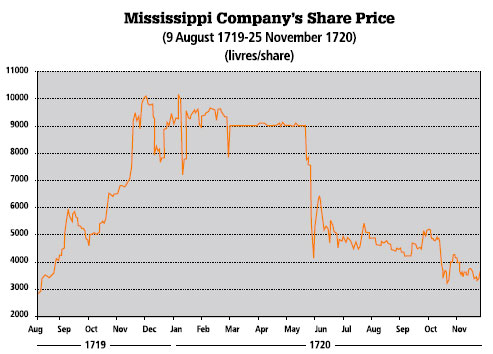

With the prospect of spectacular returns, Paris became swollen with investors from all parts of Europe. And as the accompanying chart indicates, the price of the Mississippi Company’s shares soared. So did Law’s fortunes. Among other things, in December 1719, he was appointed Controller-General of Finances—a position that made him the virtual Prime Minister of France.

Richard Cantillon (1680/90?-1734)—a great economic theorist, financier and advocate of specie-backed money—succeeded in making two fortunes from Law’s Mississippi System. The first was made on the rising market for Mississippi Company shares. Cantillon’s second fortune was made on exchange-rate speculation. Cantillon spotted a fatal flaw in Law’s strategy: the increase in the issue of banknotes unbacked by specie that were required to put a floor under the Mississippi shares at 9,000 livres per share. Accordingly, Cantillon concluded that the monetization of Mississippi shares would result in a surge in the money supply and a sharp fall in the value of the livre against the pound sterling. In consequence, Cantillon took a large speculative position against the French currency—an action that made him a fortune and caused Law to expel him from France.

This brings us back to the present and the Law-Keynes linkage. As ever-larger stimulus packages and intervention strategies are contemplated, it might be worth reflecting on the fate of John Law’s Mississippi System.

(For a full treatment of the topics discussed, see: Antoin E. Murphy, Richard Cantillon: Entrepreneur and Economist. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1986 and Antoin E. Murphy, John Law: Economic Theorist and Policy-Maker. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997.)

Author Steve H. Hanke

0 responses on "From John Law to John Maynard Keynes"