Federal Reserve Chairman Ben S. Bernanke continues to claim that the Fed’s monetary policies had virtually nothing to do with setting off the Panic of 2008. The financial press and public have bought into the Fed’s denials of culpability.

This is par for the course. To understand why the Fed’s fantastic claims are rarely subjected to the indignity of empirical verification, we have to look no further than the late Nobelist Milton Friedman. In a 1975 book of essays in honor of Prof. Milton Friedman, Capitalism and Freedom: Problems and Prospects, Prof. Gordon Tullock wrote:

“…it should be pointed out that a very large part of the information available on most government issues originates within the government. On several occasions in my hearing (I don’t know whether it is in his writing or not but I have heard him say this a number of times) Milton Friedman has pointed out that one of the basic reasons for the good press the Federal Reserve Board has had for many years has been that the Federal Reserve Board is the source of 98 percent of all writing on the Federal Reserve Board. Most government agencies have this characteristic…”

Prof. Friedman’s assertion has subsequently been supported by Prof. Larry White’s research. In 2002, 74% of the articles on monetary policy published by U.S. economists in U.S.-edited journals appeared in Fed-sponsored publications, or were authored (or co-authored) by Fed staff economists.

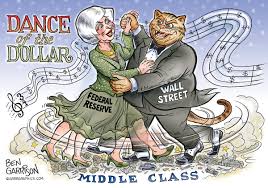

Not all economists have been willing to turn a blind eye towards the Fed’s role in triggering the Panic of 2008, however. Nobelist Robert Mundell concludes that, during the second half of 2008, U.S. monetary policy was ultra-tight and that this forced Lehman Brothers and others to go to the wall. Prof. Mundell observes that after July 2008 the dollar soared against the euro and commodity prices collapsed. According to him, both signaled that the Fed’s monetary policy was too tight. Contrary to the Fed’s claims, the dance of the dollar and related movements in commodity prices indicate whether monetary policy is too tight or too loose.

The linkage between the dollar-euro exchange rate and commodity prices is depicted in the accompanying chart. The dance of the dollar counts — and it counts a lot. With few exceptions, when the dollar weakens against the euro, commodity prices soar, and when the dollar soars against the euro, commodity prices plunge. Every commodity trader knows the importance of the dance of the dollar. Indeed, commodity traders know that, when the value of the dollar falls, the nominal dollar prices of internationally traded commodities — like gold, rice, corn and oil — must increase because more dollars are required to purchase the same quantity of any commodity.

To examine the linkage between the greenback and commodity prices, a counterfactual — a what if, thought experiment — is well suited. Counterfactuals are often employed to examine alternatives to actual history. For example, what would have happened if, contrary to fact, some present condition were changed?

The use of counterfactuals has a rich, if not controversial, history. Perhaps the most famous counterfactual was employed by Professor Robert Fogel of the University of Chicago in Railroads and American Economic Growth. In that book, Prof. Fogel calculated what the transportation system of the United States in 1890 would have looked like without railroads. His calculations created a great controversy. But, they were robust and helped him win the 1993 Nobel Prize in Economics.

The following tables contain the results of counterfactual calculations during the five phases of the dance of the dollar since December 2001. The first table represents Phase I (28 December 2001 — 11 July 2008). During Phase I, the dollar was becoming weaker, contributing to a boom in commodity prices. By computing what the prices of various commodities would have been on 11 July 2008 — if the dollar-euro exchange rate would have remained the same as it was on 28 December 2001 — we can determine (on a counterfactual basis) what the exchange-rate (weak dollar) contribution to the total change in various commodity prices was in the period under study. For example, rough rice prices increased by 358% and the weak dollar contributed 56.86% to the price increase of rough rice. Because the counterfactual price on 11 July 2008 (9.95 USD per cwt.) shows an increase from 28 December 2001 (3.91 USD per cwt.), we note that real factors (supply and demand fundamentals) also contributed to the price increase in the period under study. This is signified by a “+” sign in the last column for rough rice in the Phase I table.

Lean hogs are at the other end of the spectrum. If the dollar-euro exchange rate would have remained at its 28 December 2001 level, the price of lean hogs would have declined from 56.30 cents per pound to 39.59 cents per pound during the 28 December 2001 — 11 July 2008 period. In fact, the price of lean hogs was 71.25 cents per pound on 11 July 2008. Accordingly, the exchange-rate contribution to the change in the price of lean hogs in the period under study was 211.80%. Because the counterfactual price of lean hogs on 11 July 2008 (39.59 cents per pound) shows a decrease from the original price on 28 December 2001 (56.30 cents per pound), we conclude that real factors were working to depress the price of lean hogs, and that is why a “–” sign is entered in the last column for lean hogs.

By embracing inflation targeting — aiming monetary policy to hit an annual inflation rate of zero to two percent — the Fed has ignored the dance of the dollar and related commodity prices. This resulted in one of the most unstable periods in U.S. monetary history and the Panic of 2008. It is time for the Fed to put a halt to the dance of the dollar. This will require the Fed to dump inflation targeting and to start paying attention to the value of the dollar and commodity prices — like gold.

Author Steve H. Hanke

0 responses on "The Dance of the Dollar"