Zimbabwe freed its economy from the nightmare of hyperinflation by dumping its currency and adopting mainly the U.S. dollar. Six years on the economy is back in crisis.

Deflation is hindering spending and investment, factories are closing and the government is struggling to find money to pay its workers.

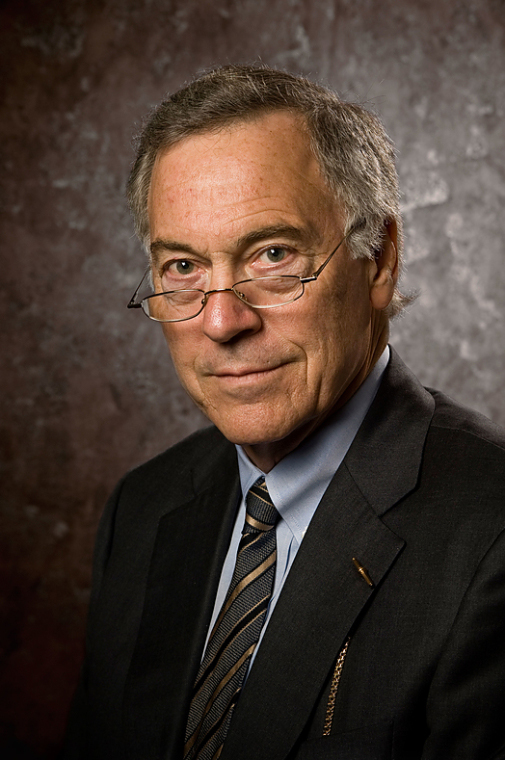

The dollar’s appreciation has made imports cheaper, exports more expensive and fueled a cash crunch, said Mark Ellyne, an economics professor at the University of Cape Town. Laws adopted in 2008 that compel foreign- and white-owned companies to sell at least 51 percent of their shares to local black investors have compounded the problem by deterring investment, he said.

“The dollar strength really works against them,” Ellyne, who worked at the International Monetary Fund for 25 years, said by phone. “They’ve made a wrong choice about the currency and they’ve not opened up enough. They should have tried to do a deal with South Africa to use the rand.”

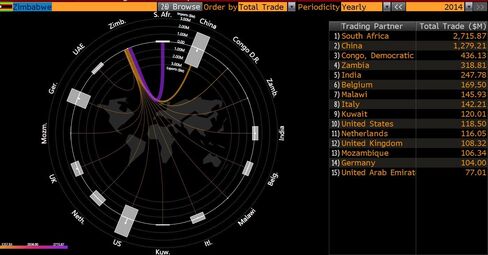

Zimbabwe imported $2.5 billion worth of goods from neighboring South Africa last year, more than from all its other trading partners combined, according to data compiled by Bloomberg. Their economies are further entwined by the estimated 2 million Zimbabweans who migrate to find jobs in Africa’s most industrialized economy, according to United Nations estimates.

Zimbabwe’s currency regime means its factories can’t compete with their South African and Zambian counterparts, according to Busisa Moyo, president of the Confederation of Zimbabwe Industries, who has called on the government to enact laws to cut salaries and utility prices. The rand has slid 26 percent against the dollar since the start of last year, while the kwacha has dived 60 percent.

Zimbabwe’s economic meltdown dates back to 2000 when militants backed by President Robert Mugabe’s government began seizing white-owned commercial farms, slashing tobacco exports. Inflation soared as the central bank printed money to enable the government to pay its bills. The Zimbabwe dollar was scrapped in early 2009 and a basket of currencies, including the dollar and rand, became legal tender. Today all pricing and about 90 percent of trade is in dollars.

Multi-Currency System

“There’s no immediate plan to return to the Zimbabwe dollar,” Finance Minister Patrick Chinamasa said by phone from Harare, the capital. “We’re tied into the multi-currency system and our focus is on creating growth.”

When hyperinflation peaked, Zimbabweans had to pay for restaurant meals before they ate and quotes from repairmen and businesses were valid for 15 minutes. With a single egg costing more than 1 billion Zimbabwe dollars, shoppers carried money in suitcases and rucksacks.

The experience still jars and few Zimbabweans favor renewed state control over the monetary system. When the central bank introduced locally minted so-called bond coins to alleviate a shortage of U.S. coins, they were widely rejected, with most people opting to take change in candy or ballpoint pens instead.

“I doubt anyone will ever trust them with money again, not after 2008,” said Fred Nyikadzino, who sells building materials in Harare. “It’s better we struggle now with a U.S. dollar they can’t control than let them print trillions and trillions of worthless money.”

Businesses Close

More than 80 Zimbabwean businesses shut last year, a trend that’s continued this year, and just 34 percent of the country’s manufacturing capacity is being utilized, according to Moyo. Consumer prices have fallen every month since March 2014, dropping 3.1 percent in September from a year ago, without boosting sales volumes. About 700,000 Zimbabweans have formal jobs, the lowest number since 1968, government data shows.

The dollar forces fiscal discipline on the government and is “a red herring” when it comes to assigning blame for Zimbabwe’s woes, according to Steve Hanke, professor of applied economics at Johns Hopkins University, who together with research associate Alex Kwok calculated that at the peak of hyperinflation prices were doubling every 24 hours.

“Companies’ lack of competitiveness in Zimbabwe is largely influenced by the difficulties created by the government’s regulatory burdens,” said Hanke, who’s also director of the Troubled Currencies Project at the Washington, D.C.-based Cato Institute. “No one knows from one day to the next what the rules of the game are and how secure their property rights will be.’’

Mugabe’s Control

Zimbabwe ranked 171st out of 189 countries in the World Bank’s 2015 Doing Business survey, which considers factors such as how easy it is to start a business, pay tax and enforce contracts. Civil servant wages swallow about 83 percent of state revenue. In August, the IMF its 2015 growth forecast in almost half to 1.5 percent.

Mugabe, 91, and his Zimbabwe African National Union-Patriotic Front party have ruled Zimbabwe since independence from Britain in 1980. Their blueprint for reviving the economy focuses on increasing the role of the state and black nationals.

“It won’t succeed because it’s premised on Zanu-PF and the government retaining control,” John Robertson, an independent economist, said by phone from Harare. “Nothing can change the direction unless they let go of the strings.”

0 responses on "Dollar Goes From Savior to Scapegoat as Zimbabwe Flounders"