The panic of 2008 has sent the political classes into fits of hyperactivity. Their favorite ploy has been to scare the public into supporting gigantic interventionist policies designed to inflate government budgets and re-regulate economic activity.

These scare tactics were on display as world leaders prepared for the London meeting of the Group of 20 on April 2. The countries represented in this grouping account for two-thirds of the world’s population and 90% of its gross national product.

After failing to predict a slow-down, let alone a panic, the International Monetary Fund finally issued a scary forecast on March 19 — just in time for the G-20 meeting. This forecast allowed the IMF to peddle its prescriptions. Once the G-20’s communiqué was released, doom and gloom were temporarily swept aside. The political classes had just struck a mother lode.

The G-20 winner was the IMF. The IMF’s managing director Dominique Strauss-Kahn — a seasoned French socialist politician — could hardly believe the IMF’s good fortune. At a press conference on April 2, Strauss-Kahn had this to say:

“Maybe some of you were in the IMF press conference at the end of the Annual Meeting last October. And if some of you were there, then you may remember that what I said at that time is that IMF is back. Today you get the proof when you read the communiqué, each paragraph, or almost each paragraph — let’s say the important ones — are in one way or another related to IMF work.”

If the G-20 summiteers come through with their pledges, the IMF’s resources will be increased by over $750 billion (USD).

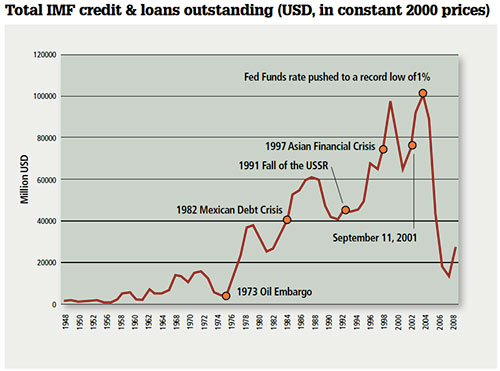

To put that in perspective, consider that the IMF’s credits and loans outstanding at the end of 2008 were only $27 billion. As politicians confront a new crisis, the opportunists are playing the system and exploiting it for their own ends.

Much of the growth of government in the US and elsewhere occurs as a direct or indirect result of national emergencies such as wars and economic slumps. Laws are enacted, bureaux are created and budgets are enlarged. In many cases these changes turn out to be permanent.

As Robert Higgs verified in his 1987 classic, Crisis and Leviathan, crises act as a ratchet, shifting the trend line of government’s size and scope up to a higher level. History provides many illustrations of how damaging this fallout can be.

Take the Great Depression. At that time, the organized farm lobbies, having sought subsidies for decades, took advantage of the crisis to pass a sweeping rescue package, the Agricultural Adjustment Act, whose title declared it to be “an act to relieve the existing national economic emergency.”

Seventy-six years later, the farmers are still sucking money from the rest of society and agricultural policy has been enlarged to satisfy a variety of other interest groups, including conservationists, nutritionists and friends of the third world. Indeed, even though agricultural prices hit record highs last year, the river of government farm subsidies kept flowing.

Then, during the second world war, when government accounted for nearly half the US’s gross domestic product, virtually every interest group tried to tap into the vastly enlarged government budget.

Even bureaux seemingly remote from the war effort claimed to be performing “essential war work” and to be entitled to bigger budgets and more personnel.

Even smaller crises have sent the opportunists into feeding frenzies. Let us return to the classic case of ever-opportunistic IMF. Established as part of the 1944 Bretton Woods agreement, the IMF was primarily responsible for extending short-term, subsidised credits to countries experiencing balance-of-payments problems under the postwar pegged-exchange rate system.

In 1971, however, Richard Nixon, then US president, closed the gold window, signalling the collapse of the Bretton Woods agreement and, presumably, the demise of the IMF’s original purpose. But since then the IMF has used every so-called crisis to expand its scope and scale (see the accompanying chart).

The oil crises of the 1970s allowed the institution to reinvent itself. Those shocks required more IMF lending to facilitate, yes, balance-of- payments adjustments. And more lending there was: in the 1970-1980 period, IMF lending increased by 123%.

With the election of Ronald Reagan as US president in 1980, it seemed the IMF’s crisis-driven opportunism might be reined in. Yet with the onset of the Mexican debt crisis, more IMF lending was “required” to prevent future debt crises and bank failures.

That rationale was used by none other than President Ronald Reagan, who personally lobbied 400 out of 435 congressmen to obtain approval for a US quota increase for the IMF. IMF lending ratcheted up again, increasing 108% in real terms during Reagan’s first term in office. With the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991, the IMF reinvented itself again. According to the IMF, a temporary lending facility was needed “to facilitate the integration of the formerly centrally planned economies into the world market system.”

The 1990s ended with the Asian Financial crisis (among others) — one that was misdiagnosed and made worse by the IMF’s medicine. Never mind. The Asian crisis was yet another justification for more funding. During the 1990- 1999 period, IMF lending increased by 99% in real terms.

Not surprisingly, the events of September 11, 2001 did not catch the IMF flat-footed. On September 18, Paul O’Neill, the then US Treasury Secretary, had breakfast with Horst Kohler, the then IMF’s managing director, to discuss the financial needs of coalition partners.

The IMF received a bit of a post-September 11 bounce. Then the IMF experienced a free fall, when the Federal Reserve (along with other central banks) pushed interest rates to record lows. The flood of new global credit was drowning the IMF until the credit bubble burst. That is when the IMF seized its opportunity.

The ratchet, of course, has many deleterious dimensions that reach well beyond public budgets. For example, on the same day the G-20 met in London, the US Financial Accounting Standards Board caved in to pressure exerted by the US Congress and altered the accounting rules for banks and other financial institutions.

Instead of valuing assets at prices they can fetch in the market (mark-to-market), banks will be allowed to use their own valuation models to value assets.

This accounting change brings to mind the fallout from another panic — the US panic of 1873. It was then that the publication of bank statements was suspended on the hope that “what you don’t know won’t hurt you.”

Let’s hope the current tidal wave of interventionism fades and a modicum of reason kicks in.

Author Steve H. Hanke

0 responses on "Panic Fallout"