At forst glance the 2001-03 plunge in U.S. interest rates seemed to have delivered the goods: Growth in output and employment slowly accelerated, and inflation stayed within the Federal Reserve’s comfort zone, under 2%. However, by mid-2004 the Fed realized that the rate of inflation was creeping up after bottoming out in 2003. And so it slowly but steadily ratcheted up the short-term cost of money. The overnight money rate is back up to 5%. The screw-tightening is not necessarily over. At least that’s how Wall Street read Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke’s June 5 warning about prices.

The Fed’s standard line is that it looks at all indicators of inflation. That said, it’s no secret that the Fed’s preferred inflation gauge is the “core” measure for Personal Consumption Expenditures. This gauge, which tracks what people spend broadly (except for food and energy), over the past year has risen by only 2.1%. While this rate exceeds the Fed’s informal target of 2%, it is still low enough for the Fed to claim that inflation is contained. However, other inflation measures challenge that benign characterization. The PCE that includes food and energy, for example, has increased by 3% in the past year. The Consumer Price Index, based on a fixed basket of goods and services (energy and food included), is up 3.6%.

Moreover, there are good reasons to believe that the government’s price indexes, with or without the volatile food and energy components, are sending out artificially weak inflation signals. For example, the recent boom in housing prices doesn’t even show up in the CPI. Something called “owner’s equivalent rent” is used as a proxy for the cost of homeownership. This metric has not kept pace with house prices.

If we look at real market data, such as that generated by commodity markets, the inflation picture changes dramatically. Over the past year the price of gold is up by 51% and crude oil by 35%. Indexes that include marketclearing prices for a broad range of industrial and agricultural commodities are also up sharply. The Commodity Research Bureau’s index of 23 commodities is up 15% from a year ago. Whether we look at government statistics or market prices, it’s pretty clear that the Fed pushed on the money-credit accelerator too hard and for too long.

As I mentioned in my Dec. 8, 2003 column, government statistics, like the PCE and CPI, lag behind changes in commodity prices. Accordingly, I expect further increases in the government’s inflation metrics and more Fed tightening. If you didn’t follow the investment advice in that column, do so now: Dump your conventional bonds and replace them with Treasury inflation- protected securities (Tips). Put 10% of your portfolio in commodities, gold being an ideal choice.

Excessively low interest rates and excess credit have generated other distortions and imbalances. Those schooled in the business cycle models developed by Friedrich Hayek in the 1930s know that excessively low interest rates result in a widening gap between savings and investment. People are unwilling to postpone consumption if the return to savings is meager, and users of capital are too prone to finance borderline projects when the cost of money is low. Sure enough, gross savings was 16.7% of gross national product in 2000.

By 2005 it had fallen to 13.8% of GNP. Gross investment (that’s investment before a deduction for capital consumption) as a percent of GNP held its own during this period, starting at 20.7% and ending at 20%. Consequently, the savings-investment gap ballooned from -4.0% of GNP to -6.25%.

At the national level, that savings minus investment in the U.S. is equal to U.S. net foreign investment. And this is equal to the balance on the U.S. current account, which is broadly the difference between U.S. exports and imports. If domestic investment exceeds total savings by Americans, as it now does, imports will be greater than exports, and we will acquire foreign capital to finance the difference. In simpler terms, our increasing trade deficit is a function of the negative differential between our saving and investment rates.

The politicos, predictably, blame the Chinese for our trade deficit. And why not? What American politician has ever lost an election by blaming foreigners for a problem made in the U.S.A.? Expect more China bashing, more mercantilist policies and an increasingly vulnerable dollar.

Author Steve H. Hanke

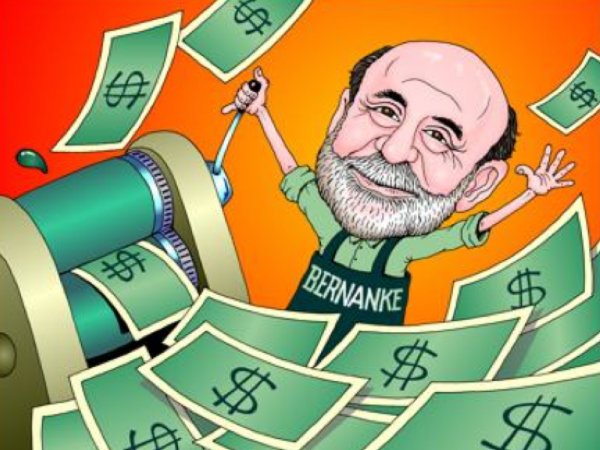

0 responses on "Bernanke’s Little Problem"