Most people think the overthrow of Saddam Hussein resulted from the U.S. government’s embrace of a new policy. This particular policy may be new, but the regime change idea and its use are not.

It is well known that Paul Wolfowitz, America’s Deputy Secretary of Defence, and a small group of like-minded neoconservatives, developed the regime change idea some time ago and have been promoting it ever since. Saddam Hussein was not the first to fall in the crosshairs of that policy. When the U.S. government concluded that Philippine president Ferdinand Marcos was illegitimate, he had to go. Consequently, America actively assisted in his removal from power in 1986. The point man who engineered the overthrow of Mr. Marcos was Paul Wolfowitz, America’s assistant secretary of state at the time. And during Mr. Wolfowitz’s tenure as the U.S. ambassador to Indonesia in 1986-1989, he planted the regime change idea once again. This time president Suharto was in the crosshairs. He was deemed to be corrupt and undemocratic and had to be overthrown. America, with the help of the International Monetary Fund (IMF), eventually accomplished its goal in 1998, when Mr. Suharto was toppled.

As it turns out, I know something about the overthrow of Mr. Suharto. In late January, 1998, I delivered a series of lectures at Bogazici University. One evening, as Mrs. Hanke and I were relaxing at Istanbul’s Ciragan Palace Hotel, I received an urgent message. It was an invitation from president Suharto to visit him in Jakarta.

The Asian crisis of 1997 hit Indonesia hard. The IMF responded by prescribing its standard medicine, and Indonesia floated the rupiah on July 2, 1997. The results were catastrophic. The value of the rupiah collapsed, inflation soared and economic chaos ensued. Mr. Suharto was aware that I had advised Bulgaria and Bosnia to establish currency boards in 1997. And like night follows day, currency chaos was halted in Bulgaria and Bosnia immediately after they adopted fixed exchange rates coupled with the full backing of their domestic currencies with foreign reserves.

President Suharto realized that the IMF’s medicine was killing the patient and that a currency board might prevent a complete collapse. Following our first meeting in Jakarta, Mr. Suharto named me his Special Counsellor. Shortly thereafter, I proposed a currency board for Indonesia, and Mr. Suharto endorsed the idea. This sent the Indonesian rupiah soaring. It appreciated 28% against the U.S. dollar on the day the news was released. This did not suit the U.S. government and the IMF.

Even though the currency board proposal gathered support from many Nobelists and other distinguished economists — including Gary Becker, Rudiger Dornbusch, Milton Friedman, Merton Miller, Robert Mundell, and Sir Alan Walters — it was subjected to a withering and ruthless attack. Mr. Suharto was told in no uncertain terms — by both the president of the United States, Bill Clinton, and Michel Camdessus, then the managing director of the IMF — that he would have to drop the currency board idea or forego $43-billion in foreign assistance.

Why did a currency board for Indonesia cause such a violent reaction? Nobelist Merton Miller understood the great game immediately. He told the Christian Science Monitor newspaper that the United States wanted to overthrow Suharto and that a currency board would spoil that plan. Prof. Miller said that the U.S. Treasury knew that a currency board would stabilize the rupiah and the Indonesian economy, and as a result, Mr. Suharto would stay in power. Consequently, the U.S. government used all means available — including the IMF — to oppose the idea. Australia’s former prime minister Paul Keating arrived at a similar conclusion: “The United States Treasury quite deliberately used the economic collapse as a means of bringing about the ouster of President Suharto.” Former U.S. secretary of state Lawrence Eagleberger embraced a similar diagnosis, too: “We [the U.S. government] were fairly clever in that we supported the IMF as it overthrew [Suharto]. Whether that was a wise way to proceed is another question. I’m not saying Mr. Suharto should have stayed, but I kind of wish he had left on terms other than because the IMF pushed him out.”

Even Michel Camdessus could not find fault with these assessments. On the occasion of his retirement, he proudly proclaimed: “We created the conditions that obliged President Suharto to leave his job.”

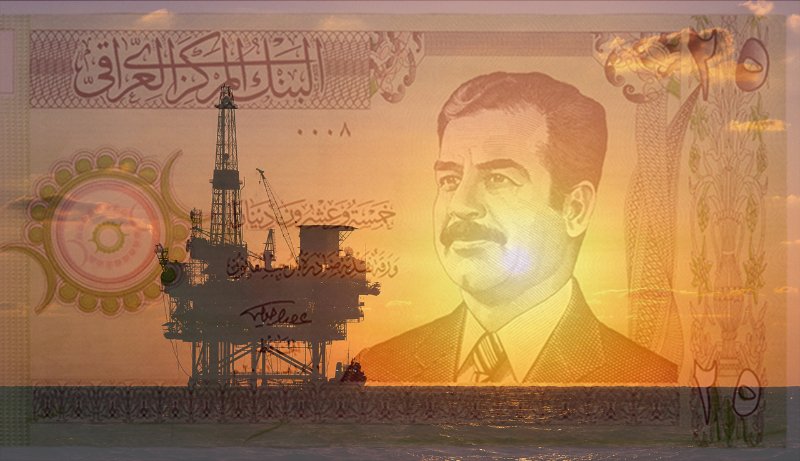

The neoconservative regime change idea and its use are not new. The only thing that distinguished its application in Iraq was the use of massive military force. Now comes the hard part: nation building. This will require (among other things) a sound currency. For that, a currency board would do the trick. After all, during the 1932-1947 period, an Iraqi currency board produced a sound and stable dinar anchored to the British pound.

Author Steve H. Hanke

0 responses on "Iraq, Regime Changes and Currency Boards"